Siege of Baghdad (1258)

| Siege of Baghdad (1258) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions | |||||||

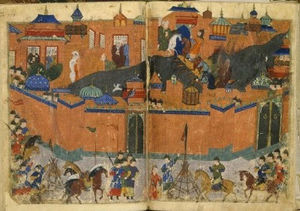

Hulagu's army conducting a siege on Baghdad walls. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire Georgian-Mongol alliance |

Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hulagu Khan Guo Kan Baiju Kitbuga Koke Ilge DavidVI ulu |

Caliph Al-Musta'sim (P.O.W.) Mujaheduddin Sulaiman Shah (P.O.W.) Qarasunqur. |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120,000[1]-150,000[2] total (60,000 Georgian people |

50,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown but believed to be minimal | 50,000 soldiers, 90,000-1,000,000 civilians |

||||||

The Siege of Baghdad, which occurred in 1258, was an invasion, siege and sacking of the city of Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid caliphate at the time and the modern-day capital of Iraq, by the Ilkhanate Mongol forces along with other allied troops under Hulagu Khan.

The invasion left Baghdad in a state of total destruction. A number of inhabitants ranging from 100,000 to 1,000,000 were massacred during the invasion of the city, and the city was sacked and burned. Even the libraries of Baghdad, including the House of Wisdom, were not safe from the attacks of the Ilkhanate forces who totally destroyed the libraries, and used the invaluable books to make a passage across Tigris River. As a result Baghdad remained depopulated and in ruins for several centuries, and the event is conventionally regarded as the end of the Islamic Golden Age.[3]

Contents |

Background

At the time Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, an Islamic state whose heart was the modern state of Iraq. The Abbasid caliphs were the second of the Islamic dynasties, having in 751 toppled the Umayyads, who had ruled from the death of Ali in 661.[4] At Baghdad's peak, it had a population of approximately one million residents and was defended by an army of 60,000 soldiers. By the mid-1200s, the caliphate had been long on the wane and was now a minor state; however, although its caliph was a figurehead, controlled by Mamluk or Turkic warlords, he still had great symbolic significance, and Baghdad was still a rich and cultured city. Before the siege by Hulagu Khan, the Mongols under general Baiju raided the modern day Iraq several times in 1238, 1242 and 1246, but not the city itself.

Composition of the besieging army

In 1257, the Mongol ruler Möngke Khan resolved to conquer the Abbasid Caliphate next after conquering and creating vassal states out of the surrounding regions. He conscripted one out of every ten fighting men in the empire for the invasion force knowing that Baghdad was a large and central area in the region. This force, by one estimate 150,000 strong, was probably the largest ever fielded by the Mongols. In November of 1257, under the command of Hulagu Khan (also spelled as Hulegu) and the Jalayir general Koke Ilge and with the Chinese commander Guo Kan in vice-command, it set out for Baghdad. [5]. It also contained a large contingent of various Christian forces, chief among which seems to have been the Georgians, who were eager to avenge the sacking of their capital, Tiflis decades earlier by Jalal al-Din Khwarazmshah.[6] Other participating Christian forces were the Armenian army, led by their king, and some Frankish troops from the Principality of Antioch.[7] The contemporary Persian observer, Ata al-Mulk Juvayni reports as participants in the siege about 1,000 Chinese artillery experts, and Armenians, Georgians, Persians, and Turks.[2]

The Siege

|

|||||

Prior to laying siege to Baghdad, Hulagu easily destroyed the Lurs, and his reputation so frightened the Assassins that they surrendered their impregnable fortress of Alamut to him without a fight in 1256. He then advanced on Baghdad.

Mongke Khan had ordered his brother to spare the Caliphate if it submitted to the authority of the Mongol Khanate. Upon nearing Baghdad, Hulagu demanded surrender; the caliph, Al-Musta'sim, refused. By many accounts, Al-Musta'sim had failed to prepare for the onslaught; he neither gathered armies nor strengthened the city's walls. Even worse, he greatly offended Hulagu Khan by threats he made, and thus assured his destruction.[8]

Hulagu positioned his forces on both banks of the Tigris River, dividing them to form a pincer around the city. The caliph's army repulsed some of the forces attacking from the west, but were defeated in the next battle. The attacking Mongols broke some dikes and flooded the ground behind the caliph’s army, trapping it. Thus were many troops slaughtered or drowned.

The Chinese contingent then laid siege to the city starting January 29, constructing a palisade and ditch, and employing siege engines and catapults. The battle was swift by siege standards: by February 5 the Mongols controlled a stretch of the wall. Al-Musta'sim begged to negotiate, but was refused.

On February 10, Baghdad surrendered. The Mongols swept into the city on February 13 and began a week of massacre and destruction.

Destruction

Many historical accounts detailed the cruelties of the Mongol conquerors.

- The Grand Library of Baghdad, containing countless precious historical documents and books on subjects ranging from medicine to astronomy, was destroyed. Survivors said that the waters of the Tigris ran black with ink from the enormous quantities of books flung into the river and red from the blood of the scientists and philosophers killed.

- Citizens attempted to flee, but were intercepted by Mongol soldiers who killed with abandon. Martin Sicker writes that close to 90,000 people may have died (Sicker 2000, p. 111). Other estimates go much higher. Wassaf claims the loss of life was several hundred thousand. Ian Frazier of The New Yorker says estimates of the death toll have ranged from 200,000 to a million.[9]

- The Mongols looted and then destroyed mosques, palaces, libraries, and hospitals. Grand buildings that had been the work of generations were burned to the ground.

- The caliph was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury plundered. According to most accounts, the caliph was killed by trampling. The Mongols rolled the caliph up in a rug, and rode their horses over him, as they believed that the earth was offended if touched by royal blood. All but one of his sons were killed, and the sole surviving son was sent to Mongolia, where Mongolian historians report he married and fathered children, but played no role in Islam thereafter (see Abbasid: The end of the dynasty).

- Hulagu had to move his camp upwind of the city, due to the stench of decay from the ruined city.

Baghdad was a depopulated, ruined city for several centuries and only gradually recovered some of its former glory.

Comments on the destruction

- "Iraq in 1258 was very different from present day Iraq. Its agriculture was supported by canal networks thousands of years old. Baghdad was one of the most brilliant intellectual centers in the world. The Mongol destruction of Baghdad was a psychological blow from which Islam never recovered. Already Islam was turning inward, becoming more suspicious of conflicts between faith and reason and more conservative. With the sack of Baghdad, the intellectual flowering of Islam was snuffed out. Imagining the Athens of Pericles and Aristotle obliterated by a nuclear weapon begins to suggest the enormity of the blow. The Mongols filled in the irrigation canals and left Iraq too depopulated to restore them." (Steven Dutch)

- "They swept through the city like hungry falcons attacking a flight of doves, or like raging wolves attacking sheep, with loose reins and shameless faces, murdering and spreading terror...beds and cushions made of gold and encrusted with jewels were cut to pieces with knives and torn to shreds. Those hiding behind the veils of the great Harem were dragged...through the streets and alleys, each of them becoming a plaything...as the population died at the hands of the invaders." (Abdullah Wassaf as cited by David Morgan)

Causes for agricultural decline

Some historians believe that the Mongol invasion destroyed much of the irrigation infrastructure that had sustained Mesopotamia for many millennia. Canals were cut as a military tactic and never repaired. So many people died or fled that neither the labor nor the organization were sufficient to maintain the canal system. It broke down or silted up. This theory was advanced by historian Svatopluk Souček in his 2000 book, A History of Inner Asia and has been adopted by authors such as Steven Dutch.

Other historians point to soil salination as the culprit in the decline in agriculture.[10][11]

Aftermath

The year following the fall of Baghdad, Hulagu named the Persian Ata al-Mulk Juvayni governor of Baghdad, Lower Mesopotamia, and Khuzistan. At the intervention of the Mongol Hulagu's Nestorian Christian wife, Dokuz Khatun, the Christian inhabitants were spared.[12][13] Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian Catholicos Mar Makikha, and ordered a cathedral to be built for him.[14]

See also

- Seljuk siege of Baghdad 1157

- Abbasid

- Baghdad

- Islamic Golden Age

- Mongke Khan

- Mongol Empire

- Soil salination

- Tigris-Euphrates river system

Notes

- ↑ L. Venegoni (2003). Hülägü's Campaign in the West - (1256-1260), Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Geographic, v. 191 (1997)

- ↑ Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis (2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today", The FASEB Journal 20, pp. 1581–1586.

- ↑ Nicolle, p. 108

- ↑ Saunders 1971

- ↑ Khanbaghi, 60

- ↑ Demurger, 80-81; Demurger 284

- ↑ Nicolle

- ↑ Ian Frazier, Annals of history: Invaders: Destroying Baghdad, The New Yorker 25 April 2005. p.4

- ↑ Alltel.net

- ↑ Saudiaramcoworld.com

- ↑ Maalouf, 243

- ↑ Runciman, 306

- ↑ Foltz, 123

References

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. 1998. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 (first edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46226-6.

- Demurger, Alain. 2005. Les Templiers. Une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen Âge. Éditions du Seuil.

- ibid. 2006. Croisades et Croisés au Moyen-Age. Paris: Groupe Flammarion.

- Khanbaghi, Aptin. 2006. The fire, the star, and the cross: minority religions in medieval and early modern Iran. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Morgan, David. 1990. The Mongols. Boston: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- Nicolle, David, and Richard Hook (illustrator). 1998. The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-407-9.

- Runciman, Steven. A history of the Crusades.

- Saunders, J.J. 2001. The History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- Sicker, Martin. 2000. The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96892-8.

- Souček, Svat. 2000. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

External links

- NewYorker.com, article describing Hulagu's conquest of Baghdad, written by Ian Frazier, appeared in the April 25, 2005 issue of The New Yorker.

- UWGB.edu, Steven Dutch article